Steel in the Symphony

It began, as these things often do, with an email from a stranger.

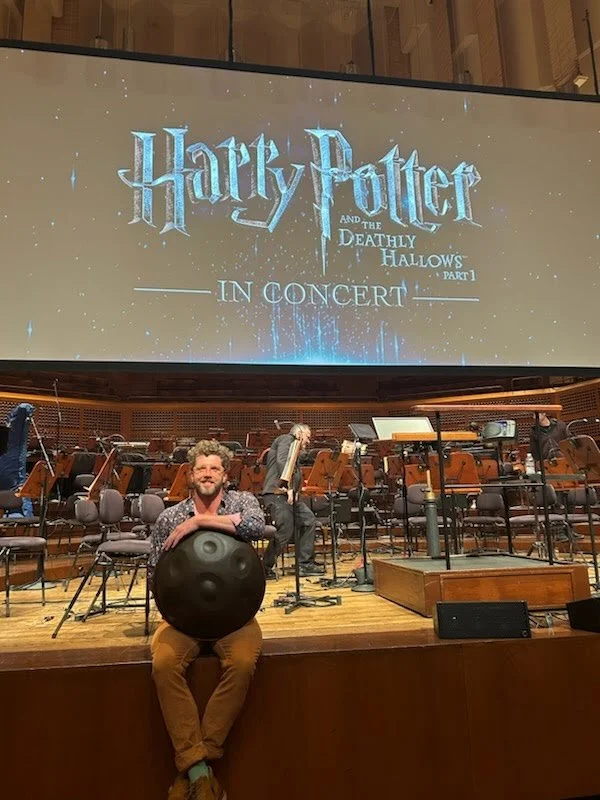

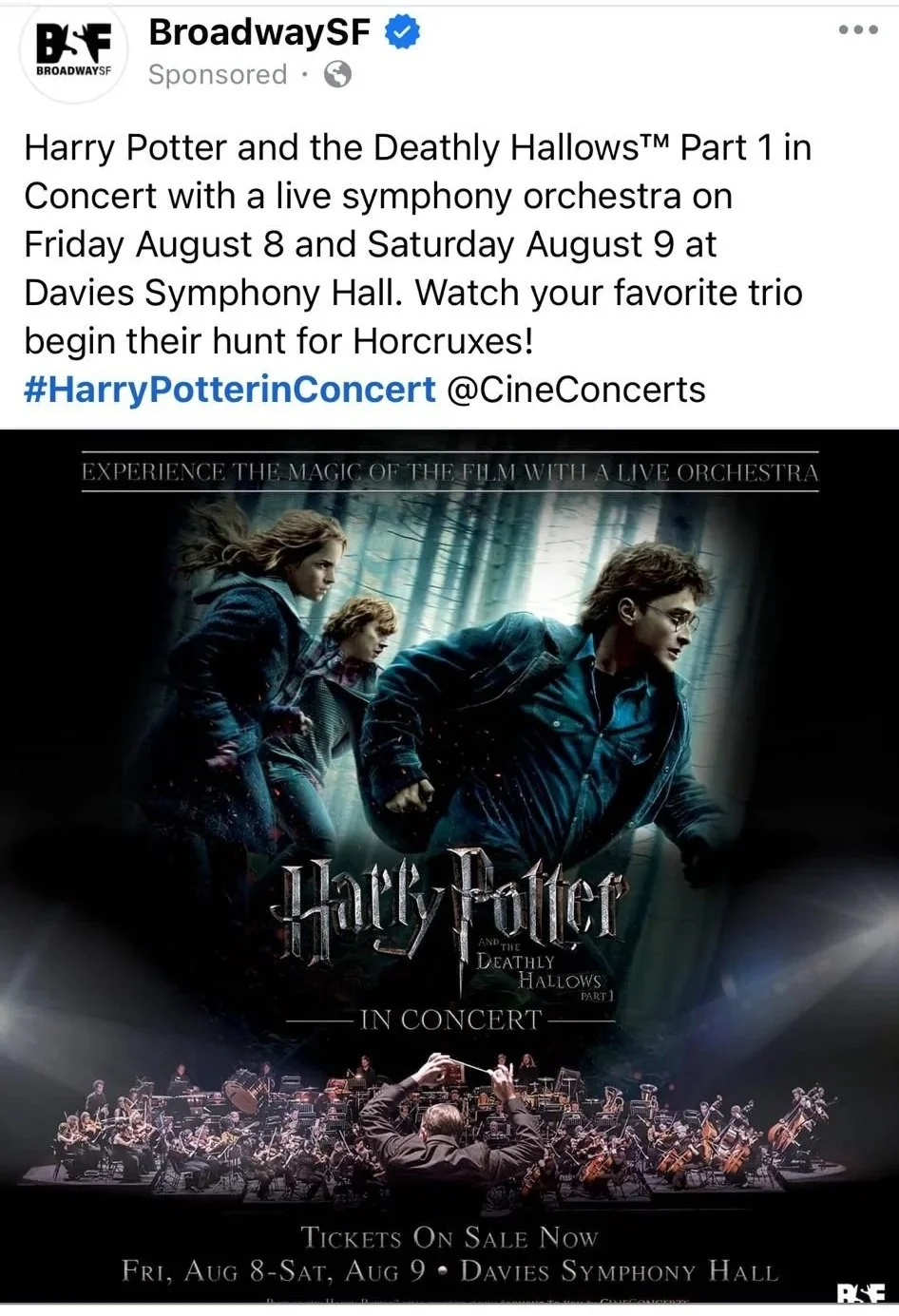

Victor Avdienko, a percussionist with the San Francisco Symphony, reached out in July with an unusual request: a handpan with the notes Eb3 and Gb3. When I asked why — such a specific request — he explained it was for an upcoming concert series: Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 1 in Concert, where the symphony plays the live score as they screen the film.

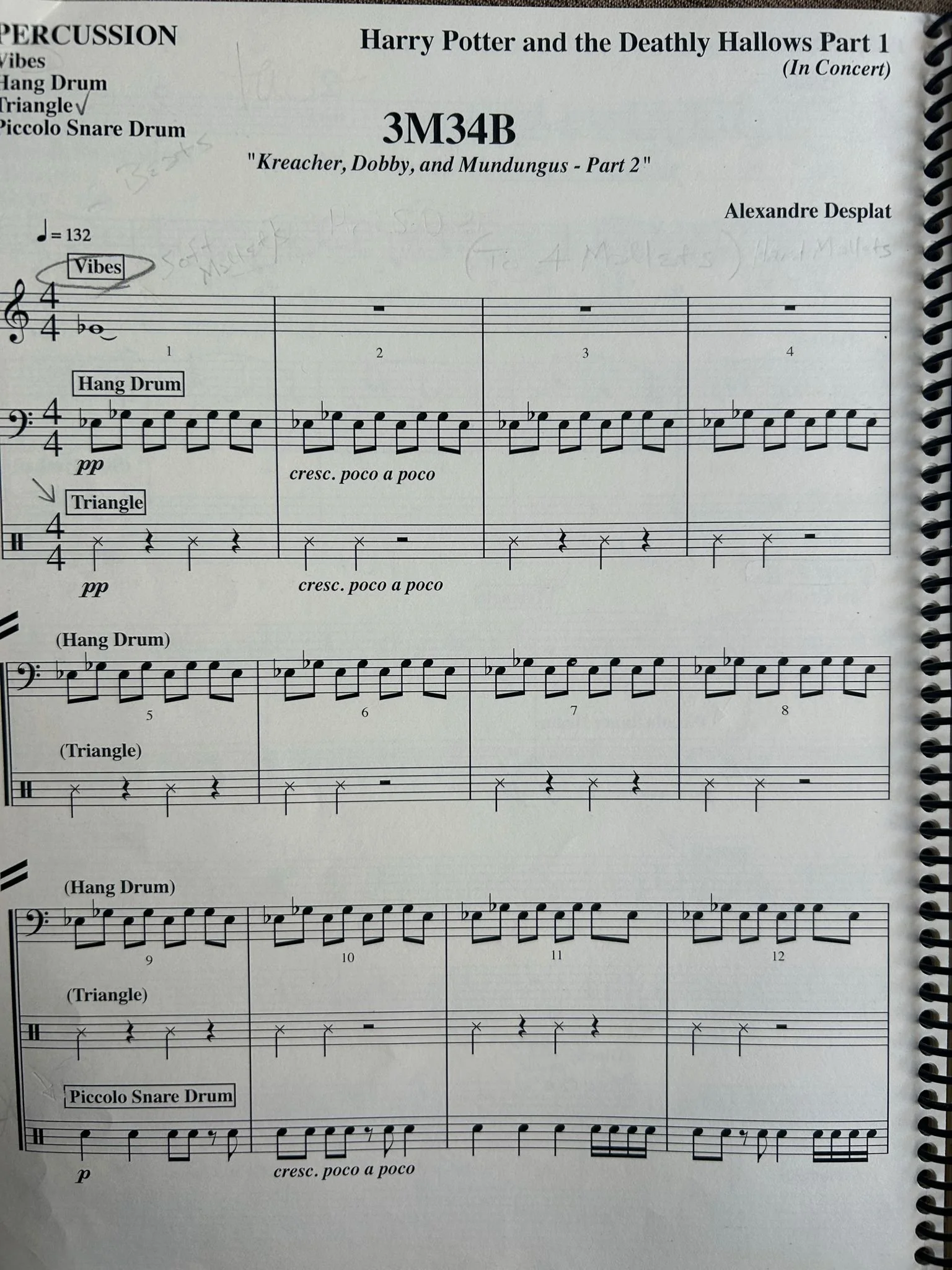

He didn’t want a steelpan, or some substitute that was “close enough.” The score called for it. The orchestra needed it. They needed a handpan.

When I first read his message, I smiled. It was the kind of request that, although not impossible, presented a unique challenge. Eb is a tough range for handpans. Not Eb itself, but its fifth, Bb — specifically Bb4. On a standard 53cm shell, Bb4 simply won’t work; the geometry of the sound chamber refuses it. Which is why you don’t see many instruments in Eb.

So if I was going to do this, I had to reach back into my own history. I dug into my archives and pulled out a shell from 2018, from the Æther days — a 50cm shell. Smaller, tighter, a leftover canvas from a bygone era, but capable of holding what eludes the standard 53cm. In some ways, it felt poetic — that to meet this once-in-a-lifetime request, I had to resurrect something from my own past.

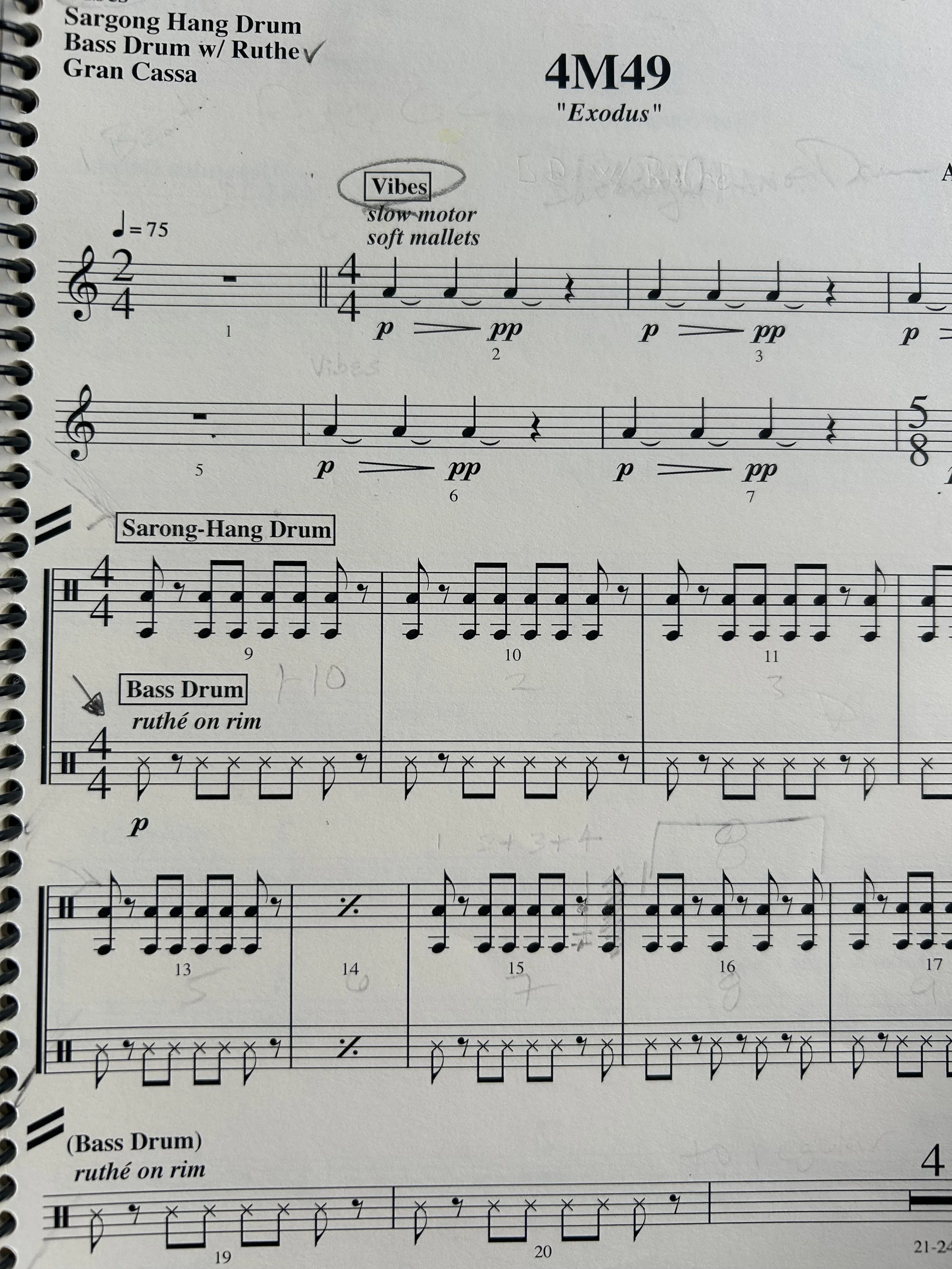

The big question was: what scale? What sound model could hold Eb3 and Gb3 as anchors? Sure the score only called for those two notes, but what could I build around them?

I ruminated for days, sketching possibilities, letting my hands work out what my mind couldn’t. Eventually, I landed on something that felt right — a scale long forgotten.

Magic Hour:

(Eb3) Gb3 Bb3 Db4 Eb4 Gb4 Ab4 Bb4

It felt like the perfect tip of the wizard’s hat to the concert series itself, and a quiet nod to a golden era gone by.

To make it, I had to brush off old tools, dies, and techniques. No rapid production methods. No magic wand to wave. Just steel, sweat, and patience.

When it was finished, I stared at it for a long time. Not just at the notes, but at the story inside them. Here was an instrument that bridged worlds:

From my shop to Hogwarts

From raw steel to Alexandre Desplat’s score.

From an obscure request in an email to a packed hall of thousands.

When Victor came to pick it up, he brought his son. I liked that. It felt fitting. We talked shop — technique, projection, resonance. He asked about what the instrument could take. I told him the truth: a handpan is both resilient and fragile. I trusted that with his experience, and my guidance, he would find his way.

A few days later, he messaged me from rehearsal: “It sounds great and the conductor LOVES it!” That was enough. That one line — the conductor loves it — told me everything I needed to know. My work had passed its trial by fire alongside centuries-old instruments. It belonged.

And then came the real thing. Two sold-out nights at Davies Symphony Hall. This was the penultimate concert, leaving only Deathly Hallows, Part 2 to complete a nearly decade-long tradition — one film a year, one performance at a time.

I grew up in concert halls. Back when I played cello, black tie and polished shoes, sweating under the lights. I knew what it felt like to sit in those seats, to glance up at a conductor’s baton and wait for the downbeat. But this time was different. I wasn’t on stage. I wasn’t backstage. I was just another face in the audience — anonymous, unremarkable. A nobody in the crowd.

And yet, part of me was on stage. My instrument was there, carrying its voice through the hall.

The first time it was heard was the first time Dobby appeared on screen. That little burst of sound — bright, specific, unmistakable — rose up out of the pit and into the story, tethering my steel to the beloved wide-eyed elf who would soon break our hearts. I couldn’t help myself: I cheered along with everyone else, swept into the joy of seeing him. For a moment, I wasn’t the maker. I was simply a fan, carried by the music.

I let myself surrender into the experience. I laughed in the light moments, gasped at the dark ones. And at the end, I clapped and hollered with the rest of them. Not for myself, not even for the handpan, but for the whole thing — the musicians, the film, the story, the shared magic of being in that room.

It was a strange kind of wholeness: to be both creator and consumer, insider and outsider. To sit as a fan while my work played its small part in something much bigger.

There’s a humility in moments like that too. Handpans are still young — barely two decades old in the lineage of orchestral instruments. They don’t yet have a “seat at the table” the way timpani or cello do. And yet, for two nights at Davies Symphony Hall, there it was. Nestled between the taiko and the vibraphone, not as a guest, not as a novelty, but as if it had always belonged.

Seeing the scope of the hall and the impact of the experience helped me realize this was far bigger than me. Bigger than my workshop, bigger than my business, bigger than the hours I’ve spent with hammer and steel. This was huge for the artform itself.

A handpan had found its way into the symphony. And moreover, found its place.

Sitting there, applauding until the lights came up, I realized something else: I had come full circle. The boy who once sat with a cello in black-tie halls was now the man who had supplied the instrument. I wasn’t bowing the notes anymore — I was building them. And they were ringing out in one of the great halls of the world, underscoring one of cinema’s most beloved characters in a most cherished franchise.

For me, it wasn’t just about Harry Potter, or even the San Francisco Symphony. It was about watching this instrument — our young fledgling — step into a lineage it was never meant to, and finding out that it belonged.

As if it was always meant to be there.